by Athol Fugard

Directed by Charles Randolph-Wright

Music composed and recorded by Tracy Chapman

“A contemporary classic . . . A profoundly human experience”The New York Times

Running time: 2 hours 15 minutes

OVERVIEW

Blood Knot tells the story of two brothers trapped in the madness of apartheid South Africa. One is light-skinned enough to pass for white, the other is unmistakably black. Living together in a tumbledown shack, they wrestle with the terms of their fates and dreams—and long-simmering tensions explode over a woman. A.C.T.’s new production of Fugard’s revolutionary breakthrough play, which first opened in 1961, holds a mirror up to the soul-searing effects of racism while exploring the inextricable bond between brothers.

- “Gripping and provocative. . . . intensely realized performances”San Francisco Chronicle

- “Absolutely outstanding performances . . . A dramatic triumph.”Jerry Friedman, KGO Radio

- “A rare and disturbingly affecting revival”San Jose Mercury News

“Blood Knot creates a captivating racial dialog, with the sort of frank talk that tends to be homogenized in racial conversations in America. . . . it’s remarkable.”Contra Costa Times

CAST

- Steven Anthony Jones (Zachariah)

- Jack Willis (Morris)

- Robert Ernst (Understudy)

- Hansford Prince (Understudy)

CREATIVE TEAM

- Athol Fugard (Playwright)

- Charles Randolph-Wright (Director)

- Tracy Chapman (Composer)

- Alexander V. Nichols (Scenic Designer)

- Sandra Woodhall (Costume Designer)

- Kathy A. Perkins (Lighting Designer)

- Dan Moses Schreier (Sound Designer)

- Michael Paller (Dramaturg)

- Meryl Lind Shaw (Casting Director)

- Kimberly Mark Webb (Stage Manager)

- Stephanie Schliemann (Assistant Stage Manager)

MULTIMEDIA

Video

KQED’s Spark recently went behind the scenes to capture exclusive rehearsal footage and inteviews with Charles Randolph-Wright, Tracy Chapman, and the cast of Blood Knot.

Production Photos

View production photos from Blood Knot at A.C.T.

All photos by DavidAllenStudio.com.

*

WORDS ON PLAY

Insight into the Play, the Playwright, and the Production

Each entertaining and informative issue of Words on Plays, A.C.T.’s in-depth performance guide series, contains a synopsis, advance program notes, study questions, and additional background information about the historical and cultural context of the play.

Words on Plays was available for purchase in the lobby of the theater during performances or online ($12 each + postage and handling). To subscribe to the full season ($70), call 415.749.2250.

Blood Knot

Words on Plays Prepared by

Elizabeth Brodersen, Publications Editor

Michael Paller, Resident Dramaturg

Margot Melcon, Publications & Literary Associate

Ariel Franklin-Hudson, Publications & Literary Intern

Table of Contents

1. Characters, Cast, and Synopsis of Blood Knot

6. My Brother’s Keeper: An Interview with Athol Fugard by Jessica Werner Zack

13. About the Playwright

14. From Fugard’s Notebooks

18. No Place Like Home by Michael Paller

21. Director Charles Randolph-Wright on Blood Knot

28. A Guiding Hopefulness: An Interview with Tracy Chapman about Blood Knot by Jessica Werner Zack

31. A Blood Knot Glossary

35. A Little Bit about Port Elizabeth

36. Apartheid

43. A Blood Knot Timeline by Ariel-Franklin-Hudson

55. South Africa’s “Coloreds”: A Group Torn between Black and White Worlds by Alan Cowell

61. Ten Things Everyone Should Know about Race

63. Development of the Notion of Race

66. Questions to Consider

67. For Further Information . . .

Words on Plays is made possible in part by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

INTERACT EVENT

- Koret Prologue* – February 12, 5:30 p.m.: Get inside the artistic process—come early for a preperformance discussion the director and other members of the artistic staff.

- Theater on the Couch* – February 15, 8 p.m.: Join members of the San Francisco Center for Psychoanalysis for an exciting postperformance discussion that explores the psychological aspects of Blood Knot and addresses audience questions.

- Koret Audience Exchanges* February 19, 7 p.m., February 24, 2 p.m., March 5, 2 p.m.: After the show, stick around for a Q&A session with the actors of Blood Knot, moderated by a member of the A.C.T. artistic staff.

- OUT with A.C.T., February 20, 8 p.m.: LGBT night after a performance of Blood Knot features a catered afterparty and a cast meet and greet. Visit www.act-sf.org/out for more information about how to subscribe to OUT nights.

*Discussions immediately follow the designated performance and are free for ticket holders. Please note that performance times vary.

PRESS

Press Releases

- A.C.T. Tackles Big Issues in Fugard’s Blood Knot – January 18, 2008

- A.C.T. Core Acting Company Members Travel to South Africa – August 31, 2007

Reviews and Other Press

- The Politics of Love and Hate – Terry Teachout, The Wall Street Journal

- A.C.T. reprises Blood Knot with insight, grace – Janos Gereben, The Examine

- A.C.T.’s Blood Knot Taps into Outrage of Athol Fugard– Karen D’Souza, San Jose Mercury New

- Theater review: Blood Knot digs deep into racial divide – Pat Craig, Contra Costa Times

- Theater Reviews: Blood Knot – San Francisco Chronicle

- Blood Brothers – Karen McKevitt, Theatre Bay Area

- Grammy Winner Tracy Chapman Writing Music for A.C.T’s Blood Knot – Brian Scott Lipton, TheaterMania

- A tangled ‘Blood Knot’ at ACT – By Robert Hurwitt (rhurwitt@sfchronicle.com), San Francisco Chronicle, Friday, February 15, 2008

Blood Knot: Drama. By Athol Fugard. Directed by Charles Randolph-Wright. (Through March 9. American Conservatory Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco. Two hours, 15 minutes. $17-$82. Call (415) 749-2228 or visit www.act-sf.org).

“Careful where your words are taking you, man,” Morris warns his brother Zack in Athol Fugard’s “Blood Knot.” With good reason. By the end of Fugard’s excoriatingly honest drama, words and the dreams they fuel have plunged the siblings into the insidious depths of ingrained racism.

The play that first brought Fugard to international attention – after he staged it and performed in it, opposite Zakes Mokae, in Johannesburg in 1961 – “Blood Knot” has long been one of his most widely revived works. The American Conservatory Theater production that opened Wednesday, directed by Charles Randolph-Wright and adorned with an original score by Tracy Chapman, only sporadically achieves the drama’s gripping and provocative potential. When it does, though, the intensely realized performances of Steven Anthony Jones and Jack Willis cut through the air like lightning bolts.

Like most of Fugard’s best work, “Blood” is both a searing indictment of South Africa’s then seemingly impregnable apartheid system and a probing drama of uncomfortably universal themes. The blood knot that binds these biracial (or “colored”) brothers is as treacherous as it is emblematic of shared humanity. Zack (Jones) is a dark-skinned man who ekes out a living chasing black kids away from a whites-only park. Morris (Willis) is light enough to pass for white.

Having wrestled with that temptation out in the world, the punctilious, fussy Morris has returned to keep house for his live-for-today, working brother in a cramped ghetto shack downwind from an industrially polluted lake. An experiment with finding Zack a female pen pal, who turns out to be white, derails Morris’ plans for them to save enough money to escape the ghetto, and brings their fraternal racial divide to the surface to riveting effect.

Jones and Willis create a richly nuanced, captivatingly strained sibling bond, tentatively probing, broadly comic, affecting and frighteningly revealing. Randolph-Wright doesn’t always serve the drama as well. Though he paces the emotional interactions to a fine degree, he surrounds the acting with distracting directorial flourishes, as if he didn’t trust the drama to carry its own weight.

Chapman’s recorded score evokes the period well, with her lovely murmuring voice and eloquent acoustic guitar, but is overused. The music-and-projections introductions to each act help set the scene (though a knot-tying video is jaw-droppingly banal), but Randolph-Wright keeps separating out every memory or fantasy passage with heavy-handed underscoring and dramatic lighting effects (by Kathy A. Perkins) on Alexander V. Nichols’ stunningly claustrophobic shack set.

Most of these passages are beautifully staged, but they tend to break up the build of the drama and even diffuse the tension at some key moments. ACT is using Fugard’s much pared-down 1985 script, seen here in a fairly strong Marin Theatre Company staging a decade ago (in which ACT understudy Hansford Prince starred with Rod Gnapp), but the directorial intrusions bloat what cries out to be a lean and intimate experience. As tempting as it may be to explain the play’s relevance to America’s overdue examination of race matters, ACT’s “Blood Knot” succeeds best when it lets the play speak for itself.

- A.C.T.’s Blood Knot Taps into Outrage of Athol Fugard – By Karen D’Souza, San Jose Mercury News, 02/15/2008 01:40:07 AM PST

Athol Fugard so potently forged his writing from the fresh wounds of political strife that his name became synonymous with the tragedy of apartheid.

In masterpieces from “Master Harold . . . and the Boys” to “A Lesson from Aloes,” Fugard turned the guts and bile of South African social injustice into great works of art. His 1961 breakthrough play “Blood Knot,” now in a rare and disturbingly affecting revival at San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater, forever established him as a voice of poetry and compassion in a time of fire.

While this early play may lack the subtlety of his most famous works, “Blood Knot” is fueled by the same gut-churning urgency that drives Fugard’s classics. Apartheid may be a thing of the past, but the playwright’s cry of outrage still rattles the soul.

Tenderly directed by Charles Randolph-Wright and gilded by Tracy Chapman’s honeyed score, “Blood Knot” unravels the tangle of race and identity that is, alas, as painfully relevant to the presidential election today as it was to Fugard’s homeland in the 1960s.

The color of a man’s skin marks his fate in Fugard’s sorrowful past. Trapped amid the corrugated steel and rotting wood of Port Elizabeth’s shantytowns (exquisitely denoted by Alexander V. Nichols’ set), two brothers find themselves shackled to each other and grimly plodding toward a bleak future.

Zachariah (Steven Anthony Jones) is the doer, his existence soiled by day upon day of backbreaking toil and

debased by the lot of a black man in a white world. Morris (Jack Willis) is the thinker, putting aside their pennies in the vain hope of outrunning their bleak destiny.

They share the same genes but not the same spirit. Zach is content to put his head down and plow ahead. Morris yearns for better life but since his skin is so light he can pass for white, his optimism blooms from a toxic spring. No matter what Zach does, he can never share in that dream. His nightmare follows him wherever he goes.

The air in the squalid shack is thick with the desperate intimacy of two people bound together against the world. They are two halves of the same whole irrevocably divided from their true selves.

Willis delicately suggests the pain that lines Morris’ face, while Jones finds the majesty in aching for beauty in an age of ugliness. These two master actors nail the musicality of the language, the cadences and lulls of the dialect.

These rhythms entice us into following wherever the brothers lead, even when their childish tugs-of-war slip into terrifying mind games that reek as foully as the industrial wasteland they call home. Fugard deconstructs the abuse of power in a bizarre role-playing ritual that smacks of Jean Genet’s “The Maids.” Morris plays the master and Zachariah the servant as the stain of racism blots their hearts.

Chapman’s mellifluous score bubbles out from under the action, like the ghost of their late mother, singing to fill the quiet. While the music threatens to overwhelm the production at the start, by the second act, her composition fits more snugly into the elegiac ecosystem of the play.

The startling realism of Randolph-Wright’s staging grounds this “Blood Knot.” The bare feet pounding on the dirt; the alarm clock sounding off in daily mockery of bone-weary limbs; the naked grief in the eyes; this is their cycle of life. The details of their perpetual oppression cut so deeply that the haunted past seems just at our heels.

‘Blood Knot’- Written by Athol Fugard, music composed and recorded by Tracy Chapman

The upshot: A sensitive revival of a play about the stain of racism under aPartheid with disturbing relevance to the here and now.

Where: American Conservatory Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco.

Running time: 2 hours 20 minutes (one intermission).

Tickets: $17-$82.

Information: (415) 749-2228 or go to www.act-sf.org.

Athol Fugard wondered for a time whether the ending of apartheid in South Africa might also put an end to his playwriting career. Most of his best-known works, starting with “Blood Knot,” the 1961 two-man play that brought him world-wide acclaim, had been set against the brutal backdrop of the racial segregation that the white minority of his native land imposed on its black majority in 1948. Would Mr. Fugard have anything of equal interest to say about the new South Africa brought into being by the demise of apartheid — and would that long-awaited deliverance from evil turn his older plays into stale period pieces? The answers can be found in two productions now playing on the West Coast, the American Conservatory Theater’s San Francisco revival of “Blood Knot” and the American premiere of “Victory,” Fugard’s latest play, which is being presented not on Broadway but in a tiny theater located in — of all places — Hollywood.

The Fountain Theatre, one of California’s best drama companies, performs in a 78-seat house whose front row of seats is three feet from the trapezoidal stage. You can’t get much closer than that, and “Victory,” an hour-long play about two angry young blacks (Lovensky Jean-Baptiste and Tinashe Kajese) who break into the home of an aging, demoralized white liberal (Morland Higgins) in the middle of the night, is well served by the miniature scale and fierce concentration of this production, which is supremely well acted by the three-person cast (Ms. Kajese in particular) and staged with relentless intensity by Stephen Sachs, the company’s co-artistic director. Mr. Fugard is capable of lapsing into didacticism, and this play swerves that way from time to time, but the close attention he pays to the inner lives of his tormented characters always pulls “Victory” back to the side of art.

Tinashe Kajese in Athol Fugard’s ‘Victory’

The natural intimacy of a house like the Fountain must necessarily be simulated on A.C.T.’s large proscenium stage, and one of the things I liked best about that company’s revival of “Blood Knot” was the precision with which Alexander V. Nichols, who designed the set, directs your eye to the pitiful one-room shack at center stage in which the action unfolds. The play itself is a rich character study in which Mr. Fugard passes the adamantine reality of apartheid through the refracting prism of Sartre and Camus to show us two black half-brothers cleaving uncomfortably together in the midst of a hostile world. The setting of “Blood Knot” is by definition political, but what takes place there is intensely, passionately personal, for what interests Mr. Fugard most is not politics but love. “You see, we’re tied together,” the light-skinned Morris (Jack Willis) tells the dark-skinned Zach (Steven Anthony Jones) at play’s end. “It’s what they call the blood knot… the bond between brothers.” A metaphor, yes, but is it essentially public or private? Part of the beauty of “Blood Knot” is that Mr. Fugard doesn’t make you choose.

I found A.C.T.’s 2007 production of “Hedda Gabler” to be competent but ordinary, but there is nothing at all commonplace about “Blood Knot.” Mr. Jones and Mr. Willis dig deeply into their long, difficult roles, and Charles Randolph-Wright’s staging is full of broad strokes of theatricality that enhance their finely wrought acting. Folk-rocker Tracy Chapman, whose music usually runs to the earnest, has written a strong incidental score that deftly evokes the bleak world of the South African townships. I wish I could have seen “Blood Knot” in a smaller house — watching “Victory” at the Fountain Theatre spoiled me — but I wouldn’t have wanted to miss either show, both of which are worth a trip from wherever you may happen to live.

* * *

- Revival of Banned South African Play Retains Powerful Message – By Elaine Laguerta, arts@dailycal.org. Thursday, February 21, 2008

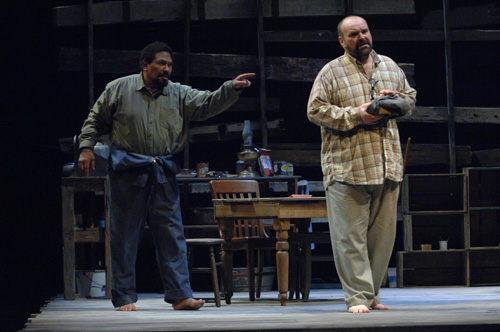

RISING TENSIONS. In Athol Fugard’s “Blood Knot,” Jack Willis and Steven Anthony Jones play brothers of different races under the oppression of apartheid South Africa.

The word “apartheid” evokes black and white images, frozen in textbooks and documentaries: black South-African protesters against white British police, boots and helmets glinting with the dark intentions of blind racism. These images carry a black and white message: The op-pressed are the good guys, the oppressors are evil.

It’s difficult to imagine a movie, play, or book that successfully reveals the reality of apartheid without these images. Even Disney couldn’t get away without a few mass demonstrations and institutional tyranny, and this in something as wholesome as “The Color of Friendship.”

I expected that a play written by a South African playwright in the 60’s, about two brothers of mixed racial background dealing with the reality of apartheid, would likely have some sort of demonstration, or at least a Grand Speech boiling down to “all men are brothers!” It’d be primarily historical, and ultimately, about having a dream. I’d walk away from the theater satisfied with my new historical and cultural knowledge. I’d clap righteously after the curtains fell, feeling en-lightened and tolerant, while condemning the evil guys in the world who would remain ignorant and racist.

“Blood Knot,” penned in 1961 by South-African playwright Athol Fugard, offers no such elementary school comfort. No staging of the familiar black and white images. No eloquent sound byte on the familiar black and white message. Not even the cast is identifiably black or white–Morris looks white and his brother Zach looks black, but they’re brothers. And there’s no stick-ing it to the man, no protests, no beatings, no martyrs. The only glimmer of a British policeman is a shiny boot in the corner of a photograph, invisible to the audience. A two-man show staged in a one-room shack, “Blood Knot” in fact contains no explicitly historical references.

And yet, without any political commentary or even mention of the word “apartheid,” it sparked a change in outlook that would metamorphose a nation. That acute bite of fresh ink, the feeling that the action on the stage won’t end with the curtain, tingled down the spines of its first audience, who flocked to a factory in a Johannesburg to witness the banned performance. Almost a half century later, with a force that spells the audience out of the velvet opulence of the Ameri-can Conservatory Theater, Morris (Jack Willis) and Zach (Steven Anthony Jones) recreate that captivation.

Today’s audience is far from that factory in Johannesburg. We laugh at how Obama is related to Dick Cheney, and view overt racism like a pass on another guy’s girlfriend-you’d better be kid-ding. If “Blood Knot” had a simple “racism is bad” message, it would not, as in 1961, intone a prayer, but simply fall on modern ears as a priest speaks to the choir. However, now as then, “Blood Knot” speaks not of history, but of existence.

The essential timelessness of Fugard’s play is that it’s not actually about apartheid. It’s about the condition of humanity-a brotherhood. Brotherhood is a relation defined not by peace or har-mony but by unbreakable ties between entities. We are brothers, like Morrie and Zach. We are inextricably each other’s keeper. Yet you are insurmountably Other.

The action moves slowly and irresistibly. Little things draw you in-like Morris musing on whom their mother loved best, the dark child or the light; or those few minutes that the brothers exclaim over the photograph of Zach’s pen-pal, “18 years old and well-developed,” before real-izing that she is white. When you’re in the thick of it, Morris is prophesying that the thought of a pretty white girl that will cause the police and their boots to punish Zach with their ways and means, and their mean ways. Later, you realize that they are locked in each other’s death grip each looking at the other with hate in his eyes, and that such a simple staging of two men talking in a room has brought you unawares and neck-deep in the inescapable.

Willis and Jones’ “acting” was so uncannily realistic that it is better called “hypnosis.” At a mesmerizing climax, during a contrived, yet seemingly harmless role-playing game, Morris and Zachariah transform imperceptibly and horrifyingly into a British “gentleman” who spits, curses, and savagely beats his black “boy.”

Their performance was strong enough to offset the well-intentioned, but ultimately bad idea to have a slide show of the aforementioned textbook images artfully overlapped by two female hands tying, of all things, a sailor’s blood knot. Also misguided was the application of Tracy Chapman’s music-though pretty, and evocative of their mother’s presence, the use of guitar-and-vocals folk music to enhance such a stark production was forced. Fugard’s lean dialogue said everything that needed to be heard. One of this production’s additions worked: The beautiful lighting over a lovely silvery abstraction of a shanty-town shack’s rough surface was director Charles Randolph-Wright’s tasteful modern enhancement.

“Blood Knot” plays at the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco from February 8th to March 3rd. Kids, don’t try the intense, unflinching dissection of your human relationships at home.

- Blood Knot – Insidebayarea.com

Athol Fugard’s “Blood Knot” comes from a terrifying place, and I don’t mean the apartheid-dominated world of South African in the early 1960s, when the play was written.

The horror of “Blood Knot” is deeply human. It comes from that potential in each of us to be a monster, to let our better selves be trapped by fear, hatred, violence and lust for power.

At the center of the play — now receiving a sturdy production from American Conservatory Theater directed by Charles Randolph-Wright — indeed its only inhabitants, are brothers Morris and Zachariah living in a Port Elizabeth shack.

Zach (Steven Anthony Jones) is dark-skinned and spends his days at an arduous, demeaning job that takes a heavy mental and physical toll on him. Morrie (Jack Willis) is much lighter-skinned — you might even say he’s white — and though he was gone for many years, he has been living with his brother for about a year, cooking, cleaning and preparing Epsom salt foot baths at the end of a long work day.

Jones and Willis bump through the first act making us believe they are brothers, but don’t fully pull us into their world. But in Act 2, their connection to each other and to the ferocious emotions is seismic.

The fact that the men are brothers means they can get to troubling places in one another faster than just about anybody else. They can hurt each other — and, conversely, help heal each other — with alarming efficiency.

The bleak world of the South Africa the brothers inhabit is effectively evoked in the design, but the most evocative aspect of the production is the music by Tracy Chapman. Mostly underscore, some instrumental, some with vocals, the music is filmic and powerful. At the top of Act 2, Chapman sings (on tape) a beautiful song about the heart of every man while we see video images of South Africa. It’s a glorious moment.

“Blood Knot” continues through March 9 at the American Conservatory Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco. Tickets are $17-$82. Call 415-749-2228 or visit http://www.act-sf.org.

Steven Anthony Jones, left, and Jack Willis are excellent as brothers in A.C.T.’s production of Athol Fugard’s “Blood Knot.” Feb 22, 2008 9:42 PM (9 hrs ago) by Janos Gereben, The Examiner

SAN FRANCISCO (Map, News) – Perplexing, intriguing, engrossing, Athol Fugard’s 1961 “Blood Knot” is one of his best plays. The American Conservatory Theater’s production focuses attention once again on the puzzle represented by the juxtaposition of the date and the judgment in the sentence above. Fugard was not yet 30, “Blood Knot” was his first substantial play — and it turned out so well, fully equal of his works to come years later: “Sizwe Banzi is Dead,” “Master Harold…and the Boys” among them.

The subject, as in all the white South African playwright’s works, is the suppression of the racist country’s black citizens. And yet, even more than in other Fugard plays, this heavy subject is not getting a heavy-handed treatment — there is psychology and deep insight into humanity (and lack of it), rather than preaching from the soapbox of the stage.

One of the play’s great accomplishments is in making its bold minimalism work so well. Two brothers — one black, the other lighter skinned — live and struggle together; they become embroiled in a potential disaster from starting a pen pal correspondence with a white woman.

A simple story, a cast of two — now that’s truly minimal, but the writing, Charles Randolph-Wright’s surehanded direction, Alexander V. Nichols’ unit set, and — especially — the acting (Steven Anthony Jones, playing Zachariah, and Jack Willis, his brother Morris), with Tracy Chapman’s affecting original music written for the San Francisco production, combine for something considerably larger than the sum of its parts.

There are elements of “Waiting for Godot” and “Of Mice and Men” in the play, but “Blood Knot” (the symbol of the brothers’ unalterable belonging together) is all Fugard.

Blood knot — a strong knot used for tying fishing leaders together — is also called a barrel knot, but that just won’t do here. This knot, with the ropes tied around each other several times for strength two or three times, has the power of shared blood in it.

Morris, who apparently — it’s just a hint — tried to pass for white, returned to the pair’s shack, devoting himself to take care of the less educated, less focused Zach. The knot works both ways, and Zach pulls back Morris from the edge of despair.

Without speeches or pearls of wisdom, “Blood Knot” leaves the audience with a cathartic realization that brothers who are different in skin color or ability are still brothers above all —and perhaps that is true beyond the confines of the stage.

Flawless, strong delivery from the two actors does wonders for the production. One mild problem is Willis’ taking on and dropping (mostly the latter) the accent that would qualify him as a resident of Port Elisabeth, at the southern tip of the country. It would be less distracting if he stuck with only a slightly modified American accent, but consistently, especially because consistency is present in all other aspects of this laudable production.

IF YOU GO

Blood Knot

Where: American Conservatory Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays; 2 p.m. Wednesdays, Saturdays-Sundays; 7 p.m. some Sundays, closes March 9

Tickets: $20 to $80

Contact: (415) 749-2228 or www.act-sf.org

Backstage magicians

- BEHIND THE SCENES, THEY CAN TRANSFORM BLANK SPACES INTO ELABORATE FANTASIES – By Karen D’Souza, San Jose Mercury News,03/02/2008 01:39:09 AM PST

Tensions between brothers Zach (Steven Anthony Jones, left) and Morrie (Jack Willis) flare up…«1»

Long ago, staggering technical firepower was strictly the province of Broadway, where falling chandeliers (“Phantom of the Opera”) and flying helicopters (“Miss Saigon”) became icons of hits on the Great White Way.

Then came Julie Taymor’s visual fantasias (“The Lion King”) and Cirque du Soleil’s phantasmagorias (“O”) that raised the bar on the eye-popping genre for good.

Now we live in a society that not only craves spectacle but outright demands it. We expect to be blown away by backstage magic. As the culture becomes magnetized by eye candy, from huge plasma screens to mini iPod videos, the visual aesthetics of set design, costumes and lights have stolen much of the spotlight. As more and more theaters break out the big bucks for yowza special effects, the stagecraft of the theater has taken center stage.

Consider the hypnotic rain effect in “Tranced,” which just closed at San Jose Repertory Theatre. Kris Stone’s liquid set design echoed one of the key themes of the play, the fluidity of identity, with a windowpane snaked by ever-flowing rivulets of water. Transparency was the motif.

“The rain effect came from many of the repeated references to water in the play,” says Kirsten Brandt, San Jose Rep’s associate artistic director. “The actual running of water was used to underscore the ‘trancing,’ the flow of thought, the flow of ideas in the play.”

Crafting such a lovely image means hammering out the mundane details of running

water onstage (how do you muffle the sound? how to keep the water from growing algae?) Just getting the acoustics of the effect right is a science of its own. All these details must be just so to turn a 12-foot-tall roll of plastic into a magic portal of light and shadow.

As technical director at the Rep, Erik Sunderman engineers the nuts and bolts behind such pageantry: “This was such a large water wall that we didn’t how we were going to make it work, but we did.”

Costume changes

Or take the decadent Weimar-era costumes that dot the American Musical Theatre’s upcoming revival of Kander and Ebb’s dark masterpiece “Cabaret.” The Bard tells us clothes make the man, so it’s the costume designer who unlocks the identity of a character in our mind’s eye.

Forget the dissipated heroin chic of Sam Mendes’ hot Broadway revival; AMT’s high-glam production celebrates the timelessness of bling. Metallic accents of silver and gold take the spotlight here instead of the usual stark black lingerie look. For uber-diva Sally Bowles, glitz and green nail polish are must-have accessories.

“She’s a bohemian,” says AMT costume designer Thomas G. Marquez. “She can wear a fur coat over pajamas and go shopping. With a little bit of lipstick, you can get away with anything.”

Of course, not all stagecraft lives in the eye of the beholder. Tracy Chapman’s score for “Blood Knot” definitely deserves star billing. The musical composition has a huge impact on the flow of this American Conservatory Theater revival. While Chapman’s honeyed sound sometimes upstages the ensemble, the score also forces us to listen to Athol Fugard’s breakthrough play, which first debuted in 1961, with fresh ears.

“Tracy’s score for ‘Blood Knot,’ ” says Carey Perloff, artistic director of ACT, “is beautifully true to the source, yet her haunting voice brings the play squarely into our own moment. So it is both honest historically but vividly immediate.”

Protecting the script

Still, there’s a fine line between enhancing the aesthetic of the text, the music of the language itself, and eclipsing it entirely.

“There is certainly a danger of a sound score overwhelming or altering the intention of a play,” notes Perloff, “but Tracy is such a consummate artist that she made sure she got deep inside the play and didn’t get in its way.”

Some theater artists certainly fear that the magic of special effects can lead to an addiction to gimmicks. The impulse to throw money at the stage, instead of letting the text speak for itself, can diminish the integrity of the art form.

For Kit Wilder, associate artistic director at San Jose’s scrappy little City Lights, where big-ticket effects are off the table, high-tech razzle-dazzle can steal attention from the spoken word.

“In my mind, unless the production is purely a showcase for the technical aspects of presentation, then the technical exists to augment, enhance, and highlight for the audience what is (or must) be there already – in the text, as interpreted and delivered by directors, actors, and the like – and must in no way obscure the story.”

Marquez couldn’t agree more. He may be a fashionista at heart but he despises sequins for sequins sake.

“Sometimes less is more,” says the costume designer. “You can put too much on someone and fuss it up like a Barbie Doll and just distract the audience.”

There is also the risk of spoon-feeding the audience, of telegraphing the message of the play, or the key to a character’s psyche, so loudly that there is nothing left for theatergoers to discover on their own.

“After all, we are all storytellers. Technical theatre becomes increasingly seductive every day, but it must never be allowed to seduce us away from the ‘committed relationship’ that we do, and must, have with story, story, story,” Wilder says. “This allows the audience to do their part: to engage their imaginations and truly bring the stage story to life in their own minds.”

‘Cabaret’, review by Karen D’Souza

Book by Joe Masteroff, music by John Kander, lyrics by Fred Ebb; presented by American Musical Theatre of San Jose

Where: Center for the Performing Arts, 255 Almaden Blvd., San Jose

When: 8 p.m. Thursdays through Saturdays; 2 p.m. Saturdays; 1 and 6:30 p.m. Sundays. Tuesday through March 16

Tickets: $14.75-$74

Information: (408) 453-7108, www.amtsj.org

‘Blood Knot’, review by Karen D’Souza

Written by Athol Fugard, music composed and recorded by Tracy Chapman

Where: American Conservatory Theater, 415 Geary Blvd., San Francisco

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays, 2 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays

Through: March 9

Tickets: $14-$82

Information: (415) 749-2228 or www.act-sf.org

- Blood Knot – By Chad, Theater Dogs

Thursday, February 14th, 2008 at 12:03 pm in ACT, Charles Randolph-Wright, Jack Willis, Steven Anthony Jones, Tracy Chapman, local theater, plays, theater review.

Opened Feb. 13, 2008 at American Conservatory Theater

Powerful performances tighten ACT’s Knot

Three stars (Powerful, scary)

Athol Fugard’s Blood Knot comes from a terrifying place, and I don’t mean the apartheid-dominated world of South African in the early 1960s, when the play was written.

The horror of Blood Knot is deeply human. It comes from that potential each of us has to be a monster, to let our better selves be trapped by fear, hatred, violence and lust for power.

At the center of the play, now receiving a sturdy production from American Conservatory Theater directed by Charles Randolph-Wright, indeed its only inhabitants, are brothers Morris and Zachariah living in a Port Elizabeth shack.

Zach (Steven Anthony Jones) is dark skinned and spends his days at an arduous, demeaning job that takes a heavy mental and physical toll on him. Morrie (Jack Willis) is much lighter skinned – you might even say he’s white – and though he was gone for many years, he has been living with his brother for about a year, cooking, cleaning and preparing Epsom salt foot baths at the end of along work day.

Act 1, for me, is troublesome. Fugard gives us a glimpse into the domesticity of the two men and hints at the drama to come. But aside from the writing of a pen-pal letter to an 18-year-old woman who turns out to be white and the sister of a cop, there’s more foreboding than drama.

Finally, in Act 2, we get to the dark heart of this family drama. Zach takes the money they’ve been saving to buy a two-man farm and squanders it on buying a fancy suit – complete with hat and umbrella – for Morrie to wear so he can meet the pen-pal girl in Zach’s place (a black man writing to a white woman would be unthinkable) because he can pass for white.

By forcing Morrie to play the game of “white man,” suit and all, Zach opens up a troubling episode that lays bare the brothers’ tangled race issues and leads to violence and, to put it mildly, fraternal upset.

The fact that the men are brothers means they can get to troubling places in one another faster than just about anybody else. They can hurt each other — and, conversely, help heal each other – with alarming efficiency.

Jones and Willis bump through the first act making us believe they are brothers but don’t fully pull us into their world. But in Act 2, their connection to each other and to the ferocious emotions is seismic.

Set designer Alexander V. Nichols fills the ACT stage with sheets of corrugated metal (which capture Kathy A. Perkins’ lights beautifully, especially when the men are fondly remembering a game they used to play in an old car), though most of the action is confined to the center of the stage where he creates an impressionistic shack of wooden slats.

The bleak world of the South Africa the brothers inhabit is effectively evoked in the design, but the most evocative aspect of the production is the music by Tracy Chapman. Mostly underscore, some instrumental, some with vocals, the music is filmic and powerful. At the top of Act 2, Chapman sings (on tape) a beautiful song about the heart of every man while we see video images of South Africa. It’s a glorious moment.

But the play, of course, belongs to Jones and Willis, who, for 2 ½ hours, pull us into quiet lives buffeted by storms both political and deeply personal. Their intensity, especially in the final section of the play, is astonishing, and the deeper they go, the more universal the play becomes.

Blood Knot continues through March 9 at the American Conservatory Theater, 415 Geary St., San Francisco. Tickets are $17 to $82. Call 415-749-2228 or www.act-sf.org.